It sometimes seems to me that the media environment surrounding me is getting increasingly fear inducing. Should our American predilection for gun violence have me quaking in my shoes? Is another deadly pandemic inevitable? Should I be afraid of the overwhelming consequences of irreversible climate change? Is our political system broken beyond repair? To help provide context and retain some sense of balance, I look for historical parallels and trends rather than just following the headlines or lead story:

—Colonial America had more endemic violence than we see now. Dueling with pistols was then considered a socially acceptable means of “settling” disputes. Unfortunately, firearm deaths remain among major causes of death in the U.S., with the majority of those deaths being suicides. Rates vary considerably by locality and over time. After a U.S. low of under 29,000 fatalities in 1999 and 2000, the death toll again began to climb. Starting in 2015, it increased significantly, by 2021 exceeding 48,000. However, because of population growth, the gun death rate of 14.6 gun deaths per 100,000 people in 2021 was still below the prior peak of 16.3 gun deaths per 100,000 people in 1974.

—During the 2020-2023 covid pandemic, losses were immense, but the global death toll, estimated at 5 to 6 million, was just over 10% of the estimated toll of the prior 1918-1920 influenza pandemic. Both pandemics fell far short of the catastrophic losses from bubonic plague outbreaks that wiped out about a third of Europe’s human population during the 14th century.

—Erratic weather events seem to have become more frequent, yet warning systems, preparation, and remediation resources have also improved. In 1900, a hurricane all but obliterated Galveston, Texas. The storm killed an estimated 10,000 people, primarily because there were inadequate weather warnings.

—We certainly have a current crop of crooked politicians and political shenanigans, but the respective eras of “Boss Tweed” of NYC’s Tammany Hall and later “Kingfish” Huey Long of Louisiana could run contemporary political machinations a close second.

In our current round of political theater, have we allowed ourselves too often, though, to be frightened by our supposed differences, be they political party, ethnicity, gender, or any other category? It may now sadly be a somewhat realistic fear to fear those who for political gain try to incite us to fear each other.

Our most famous U.S. political quote about the toxicity of fear comes from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inaugural address in March, 1933. Then, the nation’s economy was reeling after a 1929 stock market crash and several years of deepening economic dysfunction. FDR was a seasoned politician and also someone who had made an arduous recovery from the paralyzing polio he’d contracted in 1921. Without downplaying the dire state of the economy, he spoke to rally our citizenry by beginning with the need to reduce fear:

“So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

He then went on to outline actions for restoring trust (there’s a reason many banks have “trust” as part of their names) and for minimizing further panic (there’s also a reason that financial panics are called “panics.”)

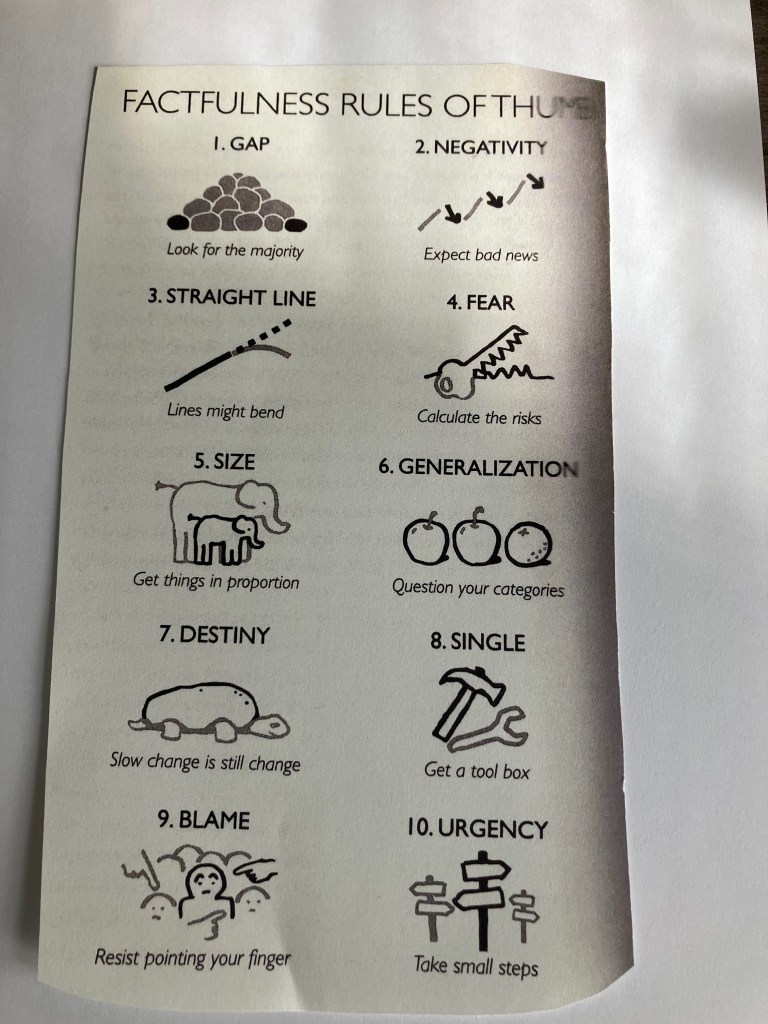

A recent explanation of the importance of not succumbing to fear comes from a 2018 book that helped get me through covid isolation: Factfulness. Authored by former Sweden-based global health researcher, professor and statistician Hans Rosling, the book evaluates a whole set of instinctual responses that can distort our human reactions to situations and events. Fear is one of the most insidious.

Anecdotally, Rosling describes his initial reaction while coping as a young emergency room physician with his first trauma event, a downed, incoherent pilot. Temporarily short of more seasoned backup, Rosling’s initial reaction was fear-driven:

“…(M)y head quickly generated a worst-case scenario. … I saw what I was afraid of seeing [a Russian intruder signaling the start of World War III]. Critical thinking is always difficult, but it’s almost impossible when we are scared. There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.”

Fortunately for Rosling and for his patient, an experienced nurse soon returned from her lunch break and identified the real problem [a Swedish pilot whose training mission had ended with a ditched plane and resulted in hypothermia]. She reclaimed the situation before the young doctor’s fear response resulted in serious errors.

Rosling also provides statistical evidence contrasting what we find frightening and what our actual risks may be: “This chapter has touched on terrifying events: natural disasters (0.1 percent of all deaths), plane crashes (0.001 percent), murders (0.7 percent), nuclear leaks (0 percent) and terrorism (0.05 percent). None of them kills more than 1 percent of the people who die each year, and still they get enormous media attention.”

Per Rosling, we all need to become better at distinguishing between what we find frightening and what is truly dangerous. He elaborates: “The world seems scarier than it is because what you hear about it has been selected—by your own attention filter or by the media—precisely because it is scary.” We need to evaluate situations based both on the actual danger and on our level of exposure to that danger.

In conclusion, he offers this suggestion: “Get calm(er) before you carry on.” Good advice for troubling times.