After another bruising electoral season, we are individually and collectively beginning to recover and move on. As an older voter, I do not expect to participate in many more presidential elections. Still, I’m concerned about the rancorous legacy our generation seems to be leaving for those who come after us.

As a grandparent, I’ve lately become one of our family’s storytellers. It’s my hope that by sharing my own family story and then by deeply listening to others, I may be able to find more common ground. I hope that we may as a community be able to diminish the worst excesses of partisan bitterness. Every family has its own instances of disasters and triumphs. My family’s stories are unique but likely not uncommon.

Some aspects of my biological family’s history remain a mystery. What has come down to me has been partially shaped by our clan’s tendency toward long generations. It’s also been shaped by a generally privileged trajectory and multiple generations of residency in what is now the United States of America.

Both sets of my grandparents were well into their sixties or seventies, living in Maryland, when I was born there in 1947. For my first eleven years, I lived next door to my maternal grandparents. That grandfather began life in 1869, so his earliest memories are from a time over 150 years ago. My other three grandparents were born in 1879. All four grandparents had stories to tell.

My maternal grandfather, the man I called Pop-Pop, was born in Mississippi just after the U.S. Civil War. He was the youngest child in a family of former slaveholders, with one older brother and five older sisters. Pop-Pop recounted being frightened of the Union troops billeted in his family home during Reconstruction. He was later able to get a good education. He spent time as a school teacher before switching to bookkeeping about the time his first child was born in 1906.

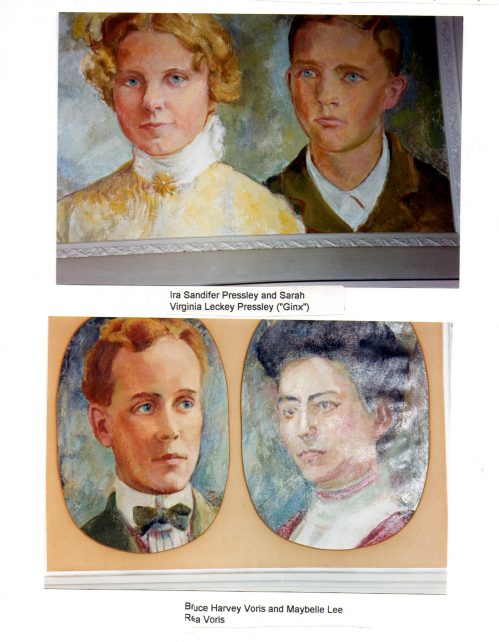

My maternal grandmother, nicknamed “Ginx,” was a 3-pound “preemie” born in January, 1879 in rural Virginia, in the days before many hospitals or “modern medicine.” Her parents later told her that for her first few months they had kept her in a makeshift incubator constructed by lining a laundry basket with warm bricks and cast-off blankets. Her father was a school superintendent in one of the counties where Pop-Pop taught school.

My paternal grandfather was the second son in a family of midwestern small-scale farmers. He met my other grandmother while both were students at a telegraphy school in Kentucky. This particular school was run by a conman whose main goal seems to have been lining his own pockets. The two lovers conducted a lengthy, partially long-distance courtship, complicated by economic struggles plus the lingering animosity between northern and southern states. Grandpa was “Yankee bred,” Grandma a Southerner. They eventually wed at my great-grandfather’s North Carolina farm at Christmas in 1907.

Grandpa and Grandma briefly attempted to homestead in Nebraska, but found the dry conditions and near-constant wind too much of a challenge. Grandpa later worked various clerical and administrative jobs, first for railroads and then for a government agency regulating interstate commerce. Grandma managed the small Maryland farm where they eventually settled and continued raising their children.

My dad made his entry into the family saga in 1912. Born in Ohio, he moved with the family to Maryland in 1920. Through grade school, he attended a two-room rural schoolhouse. By the time he was ready for college, the Great Depression had set in and money for tuition was scarce. Dad and his two older siblings took turns at the University of Maryland nearby, each finding what work they could to supplement the family income. They pooled their funds, helping each other pay college costs. Dad and his older brother John sold chickens and eggs from the farm. Aunt Lucy did clerical work.

My mom showed up in 1917 as a “bonus” daughter, eleven years younger than her sister Margaret, five years younger than her brother Stuart. Family life was hectic as the “war to end all wars” came to a close in late 1918. The armistice was bracketed by a global flu pandemic that spared Mom’s family, but killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

Aunt Margaret and Uncle Stu attended high school in Baltimore City. Though city tuition was somewhat expensive, Baltimore’s schools at the time were considered vastly superior to the small high school in the next-county village where Mom’s family lived. Pop-Pop and Granny spent much of the 1920’s ponying up city school tuition to give their children the best educational start they could. Pop-Pop had a job as a Baltimore-based bookkeeper. Granny earned money teaching piano pupils at home or in local schools. Then, just as Mom was ready to enter high school, the Depression hit. It limited Mom’s high school choices and nearly preempted her chance to attend college.

Within seven months during 1929-1930, Mom’s family experienced a one-two punch of reversals. The stock market crash in late October, 1929 did not directly impact them—Pop-Pop and Granny owned no stocks. The family’s downward spiral started about a month later with an “upward spiral.” On an unusually cold day just after Thanksgiving, a chimney fire broke out in their recently renovated kitchen. By the time the local fire brigade arrived, the fire had started to spread. They were unable to contain the blaze. Water from their hoses froze before it could reach the house’s high roof. The entire structure burned to the ground. The family found rental lodging, hoping to rebuild later. The following June, Pop-Pop, then sixty years old, was laid off from his job. The company he had worked for replaced most of their human staff with early calculating machines to cut costs.

Somehow, Mom’s family persevered. Aunt Margaret and Uncle Stu were able to find jobs. Granny took correspondence courses in hotel management. She then got work as a full-time housekeeping supervisor at a Baltimore luxury hotel. Though she frowned at some alcohol-lubricated political shenanigans during the waning days of Prohibition, she held her tongue. Pop-Pop got what temporary work he could, once surviving a major 1933 flood while working as a night guard at a railroad construction site.

Mom finished at the top of her high school class. She scraped together earnings and loans to attend college. The Depression eventually ended. Mom and Dad eventually met and married. Their “greatest generation” was partially shaped by the eras they grew up in—one global war, then boom times, then economic depression, followed by another global war. During the post-WWII baby boom, they produced me, my sister and two brothers. We’ve so far confronted different challenges, including a recent global pandemic with its accompanying trauma and dislocations.

What have been your family’s triumphs and trials? How may they influence your experience of the world going forward?